Nowadays, the best astronomical telescopes – whether large or small – are equipped to near perfection in terms of their optics, mechanics, and electronic controls. As long as there are no technical shortcomings, the way should be clear to exploit the maximum possible performance of a telescope. Unfortunately, however, there are several “enemies” that can severely limit the quality of astronomical observations. One of these is what astronomers call “atmospheric seeing.” It drastically reduces the theoretically possible image sharpness. But today there are amazing ways to combat Seeing – ways that Webservatory users can also employ.

It’s actually all relatively simple: assuming that a telescope has no other technical or optical issues and we have installed a high-tech measuring instrument such as a modern astro-camera in the focus, only one parameter determines the possible performance of the telescope: its diameter. Or more precisely: the clear aperture or size of the main mirror (or, in the case of a refracting telescope, the Entrance Lens).

As the diameter increases, more light is collected and stars that are fainter can be detected with the same exposure time. Doubling the diameter of the main mirror collects four times as much light.

In particular, the diameter also determines the theoretically possible resolution of a telescope. With double the aperture, you get double the resolution. This means that, for example, two closely spaced details on the surface of the moon or a planet or two components of a double star can only be clearly separated if their angular distance in the sky does not fall below a certain limit for a given telescope diameter. Increasing the image size (the “zoom,” i.e., the “magnification”) does not reveal any more details, but only makes the image larger, which is what the telescope offers in terms of resolution. (It should be noted here that we always assume here that the pixel size of a camera in the focus of a telescope is in any case fine enough and adjusted so that resolution is not artificially wasted (e.g., due to pixels that are too large).)

The reason for the resolving power lies in the wave properties of light. These lead to diffraction effects as soon as the radiation passes along an obstacle or through an aperture. Diffraction ensures that a perfect point source, such as a star in the focus of a telescope, is imaged as a so-called diffraction disk. The extent of this light distribution resembles a three-dimensional Gaussian bell curve and is smaller the larger the diameter of the telescope. Two closely spaced stars can therefore only be resolvd separately if the overlap of the two diffraction discs just allows them to be distinguished.

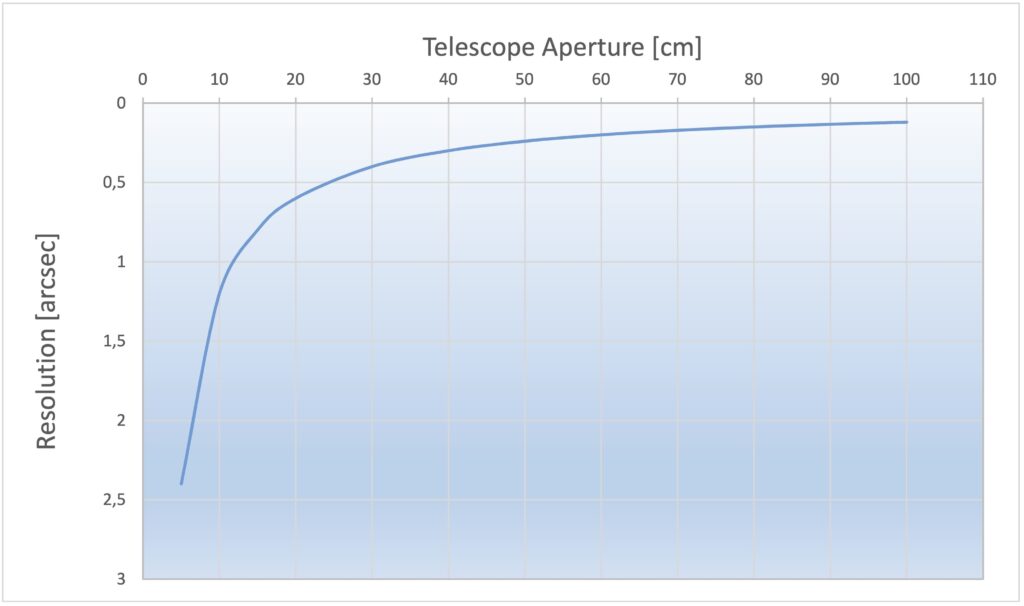

For an average wavelength of visible light, a simple rule of thumb can be used to quickly and reasonably accurately estimate the resolution of a telescope:

12/diameter [cm] = resolution in arc seconds

A telescope with an aperture of 12cm therefore reaches approximately the arc second limit in visible light. A 60-cm telescope achieves a resolution of about 0.2 arc seconds, and the Hubble Space Telescope with its 2.4m mirror achieves 0.05 arc seconds. For comparison: the apparent diameter of the moon in the sky is half a degree (= 30 arcminutes = 1800 arcseconds) and the planet Jupiter has an apparent diameter of about 40 arcsec. This means that even a relatively small telescope can reveal details on Jupiter.

The “Sharpness Killer” – Seeing

So much for the theory. Unfortunately, in practice, the aforementioned Seeing comes into play.

And it is much more serious than many laymen think. In Astronomy, Seeing refers to the blurring of images of celestial objects caused by turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere. The twinkling of the stars is one consequence of this. At a large image scale (high “magnification”) and high temporal resolution, you can see that the point source of a star not only jumps back and forth from one fraction of a second to the next, but is also constantly deformed to a greater or lesser extent.

With the longer exposures commonly used in Astronomy, e.g., for photographing faint galaxies, star clusters, and nebulae, the constantly wobbling images of a star (or any other fine detail) add up to a more or less extended and unresolved spot. And this spot is almost always much larger than the diffraction image of the star – and thus the resolution and detail sharpness achieved by a telescope is significantly lower than the theoretically possible resolution.

The bad news is that this applies to virtually all telescopes, regardless of size.

The average Seeing at a location not necessarily predestined for astronomical observations (such as in Germany) is 2-3 arc seconds. It rarely reaches one arc second (possibly on high mountains). Only at the best astronomical locations in the world, such as in Chile, on the Canary Islands, or on Hawaii, values significantly below one arc second can be achieved on a regular basis. But even there, values of 0.3-0.5 arc seconds are relatively rare.

Using the above formula, we can now quickly calculate something astonishing: even at the top locations, telescopes can at best achieve a resolution that corresponds to the diffraction limit of a 20-30 cm telescope. Without special techniques to increase the resolution, a large telescope can therefore only achieve greater light-gathering power. In terms of image sharpness, even under the best conditions, you would be limited to the level of a larger amateur telescope.

For many years, the only way to get around this problem was the extremely costly option of placing a telescope above the atmosphere – i.e., in space. And so the fantastic image sharpness of the Hubble Telescope became legendary.

Today, space telescopes remain fantastic instruments that allow us insights into the cosmos that are impossible from Earth. In addition to the naturally uncompromised image sharpness, the advantages lie primarily in the wavelength ranges that can only be used in space. The James Webb Telescope, for example, is primarily active in the infrared range, which is extremely important for scientific reasons.

In terms of resolution, however, some ground-based large telescopes can now compete or are even superior in principle—as long as it has a larger mirror diameter than a space telescope. Even though you still have to look through the atmosphere. So the question is: how is that possible? How can we outsmart the Seeing?

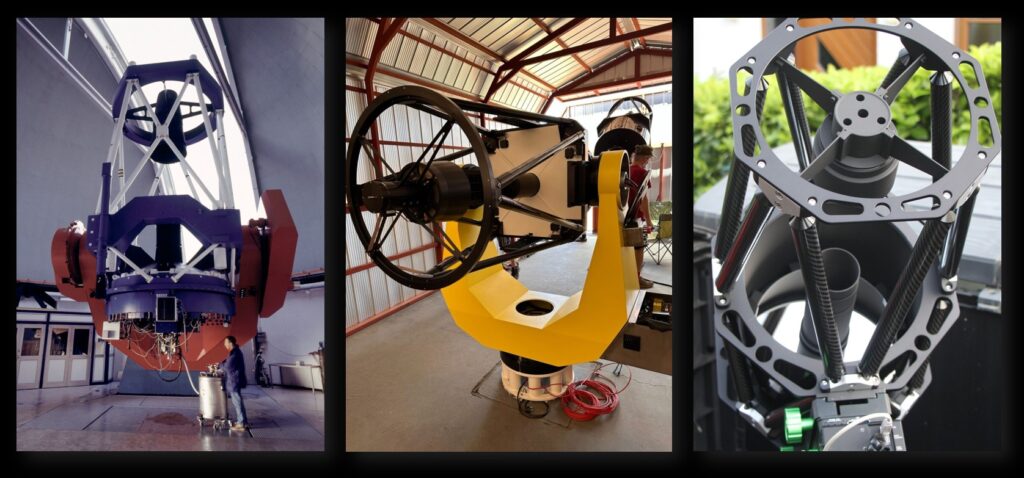

The complex and expensive solution: Adaptive Optics

A technically very complex option is to equip telescopes with Adaptive Optics. Using wavefront sensors, the image turbulence caused by Seeing can be measured using reference stars in the field of view. By controlling highly flexible, deformable mirrors in real time in the beam path, image errors can be generated that are opposite to those caused by the atmosphere. This enables corrections to be made in milliseconds, delivering a virtually perfect, sharp image at the focus of the telescope, limited only by diffraction. However, Adaptive Optics technology is not only complex and sophisticated, but also very expensive. For smaller telescopes, this is currently hardly feasible. But there is another relatively new technology that makes it possible for any telescope to at least largely overcome Seeing: Lucky Imaging!

The relatively inexpensive alternative: Lucky Imaging

Lucky Imaging makes it possible to take sharp images of the sun, moon, planets, and double stars even with small telescopes, which was impossible just a few decades ago even with the best and largest telescopes in the world. And in some cases, the technique can also be used, at least in a slightly reduced version, to capture some of the faint so-called Deep Sky Objects – i.e., objects such as star clusters, galaxies, or gaseous nebulae, which are normally only associated with long-exposure images.