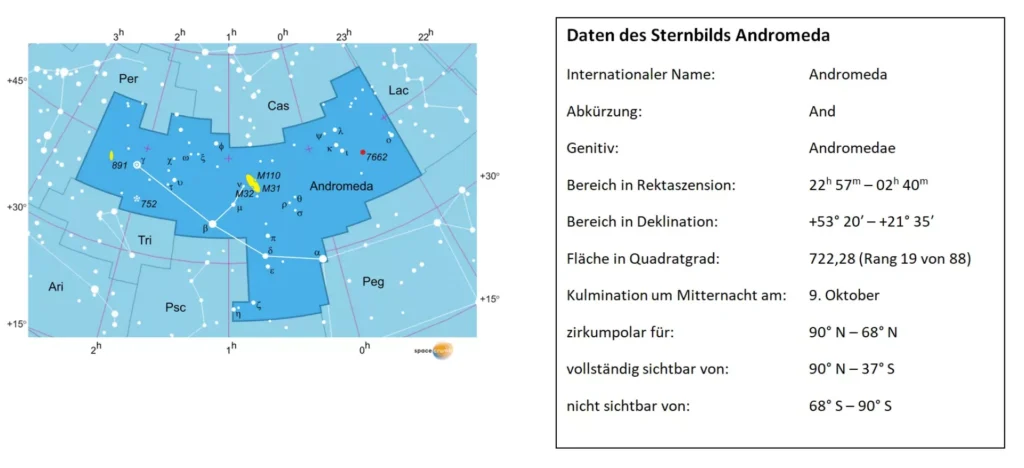

Andromeda is an expansive constellation in the northern sky. With the exception of the southernmost regions of South America and Australia, it can be observed from all inhabited areas of Earth. In the Northern Hemisphere, Andromeda is well positioned in the evening sky from August through February. For observers in the Southern Hemisphere, October is particularly favorable, as the constellation reaches its highest point in the north around midnight. Andromeda is framed by several prominent constellations: Cassiopeia to the north, Perseus to the east, and Pegasus to the southwest. To the south it borders Triangulum and Pisces, and to the west the small constellation Lacerta.

The main stars of Andromeda form a gently curved chain that begins at the star located at the northeastern corner of the Great Square of Pegasus and stretches toward the northeast. In antiquity, this corner star was attributed to both constellations. Since the modern definition of constellation boundaries, it has carried the designation Alpha Andromedae (α And), though older star charts may still list it as Delta Pegasi (δ Peg). However, it is not primarily Andromeda’s star pattern that has made the constellation so famous, but rather the large spiral galaxy located within it: the Andromeda Galaxy, Messier 31 (M 31). It is visible to the naked eye as a faint, diffuse patch of light and is easy to locate.

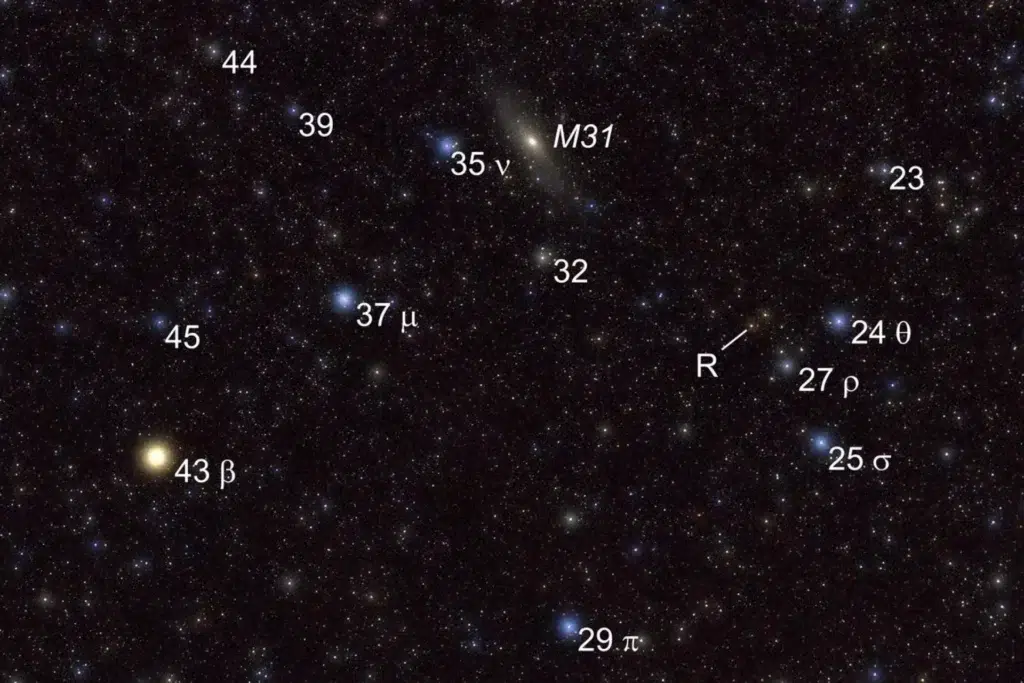

A practical way to find it is to begin at the star Beta Andromedae (β And), situated in the middle of the long star chain, and follow a fainter branch of stars that extends northward—formed by Mu and Nu Andromedae. Just 1.3° east of Nu Andromedae—roughly three times the apparent diameter of the full Moon—lies the center of the Andromeda Galaxy. While M 31 is located north of Andromeda’s bright star chain, a similarly prominent galaxy can be found at about the same distance to the south. Listed as M 33 in the Messier catalogue, this galaxy no longer belongs to the constellation Andromeda, but instead lies within the small constellation Triangulum.

The Mira Variable Star R Andromedae

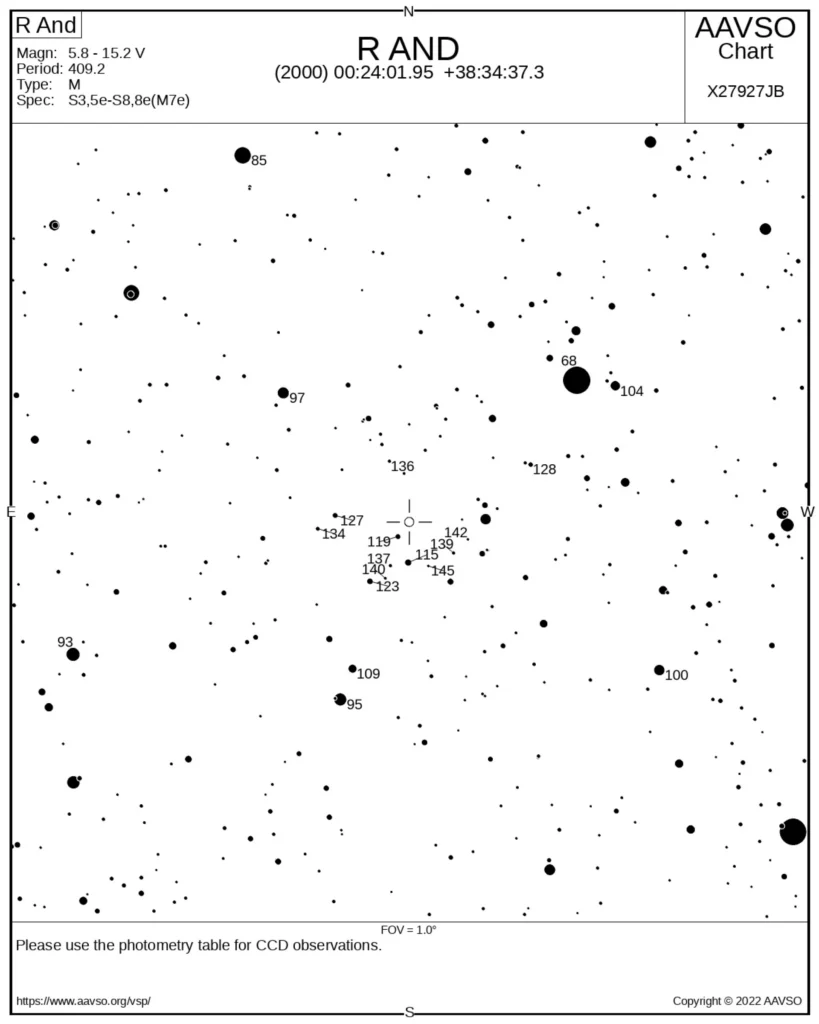

R Andromedae is a long-period pulsating variable of the Mira type located in the constellation Andromeda. It can be found 1.3° east of Theta Andromedae (θ And) and 0.8° northeast of Rho Andromedae (ρ And). In binoculars and in photographs it appears distinctly reddish. This red giant star lies just under 800 light-years away. Its apparent brightness varies over a period of 409 days, ranging from a maximum of magnitude 5.8 to a minimum of magnitude 15.2. A brightness change of nine magnitudes means that the star shines about 4,000 times brighter at maximum than at minimum. As is typical for Mira variables, the extreme brightness values can vary slightly from one cycle to the next.

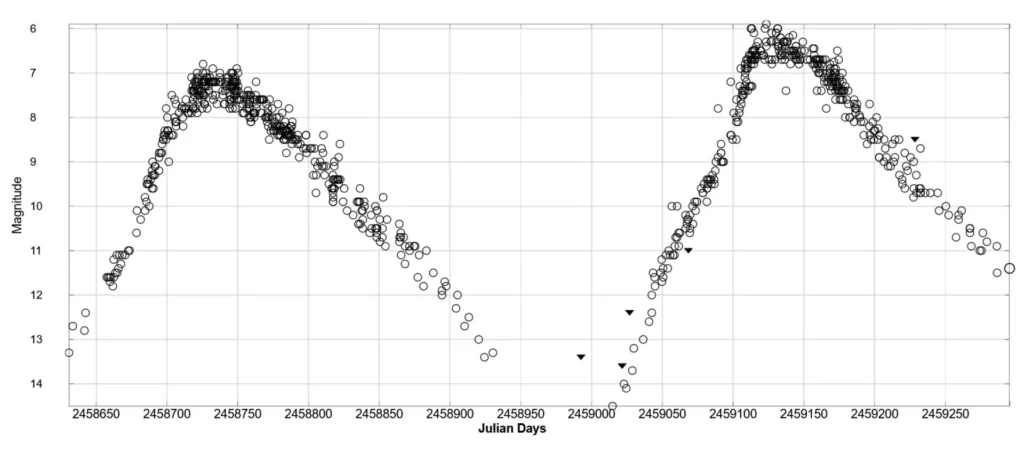

The rise in brightness occurs roughly twice as quickly as the decline; this behavior is evident in the asymmetry of the observed light curve. R Andromedae reached its most recent maxima in early October 2020 and in December 2021, each time around magnitude 6.2. In September 2019, the star remained about one magnitude fainter.

Observers wishing to follow the rise of the light curve with binoculars should begin monitoring roughly two months before the expected maximum. With a telescope capable of detecting stars around magnitude 11, the surrounding star field can be observed up to three months in advance. The star is expected to reach its next brightness maxima around the turn of the year 2022/2023 and again in February 2024.

A light curve and a finder chart with comparison star magnitudes for personal observations can be created and downloaded from the website of the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). The Bundesdeutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Veränderliche Sterne (BAV) also provides valuable information.

The light curve of the Mira variable R Andromedae shows that the apparent brightness of this pulsating star varies over a period of about 409 days, ranging from 5.8 mag to 15.2 mag, with the maximum value not always reaching the same level in each cycle. Each data point in this light curve represents a visual brightness estimate made by an amateur astronomer. The time axis, increasing to the right, is marked in units of days using the Julian Date system. (Image: AAVSO)

Technetium: A Key to Nucleosynthesis

Because of the strong absorption bands of zirconium oxide (ZrO) in its spectrum, R Andromedae belongs to the spectral class S. This special class was introduced in 1922 by the American astronomer Paul W. Merrill into the original Harvard system of spectral classification, as some red giant stars with cool atmospheres showed such distinctive spectral features.

Another remarkable characteristic in the spectrum of R Andromedae provided important insights into nucleosynthesis—the formation of chemical elements in stars—during the early 1950s. Merrill and his collaborators had obtained high-resolution spectra using the large telescopes at the Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories. In these spectra they identified, in addition to the absorption lines of heavy elements such as zirconium and barium, lines produced by technetium. This finding was surprising, since all technetium isotopes known on Earth are unstable. Some decay by half within only a few hours. The isotope technetium-98, with a half-life of 4.2 million years, is the most long-lived among them.

Technetium had been conclusively identified only in 1937, in a material sample that had been irradiated with neutrons in a particle accelerator. It was therefore the first artificially produced element, and its discovery filled a longstanding gap in the periodic table. In 1950, a research group at the U.S. National Bureau of Standards investigated the spectral properties of technetium, providing astronomers with the precise wavelengths of its spectral lines.

The s-Process

What, then, was the significance of the spectroscopic detection of technetium in the atmospheres of cool giant stars? A half-life on the order of millions of years may seem long to us, but compared to the great age of these highly evolved giant stars, it is extremely short. If technetium had been present in the original material from which these stars formed, it would have completely decayed long before the time of observation. Therefore, there had to be a mechanism capable of producing technetium inside the giant stars themselves.

Up to that point, it was only known that stars obtain their energy by fusing light atomic nuclei, forming elements such as helium, oxygen, and carbon, up to iron. The detection of technetium now provided direct evidence that stars are also able to build elements heavier than iron. The process responsible for this is the slow neutron-capture process, known to physicists as the s-process, where “s” stands for slow.

In the late evolutionary stage of these variable giant stars—characterized physically by relatively moderate temperatures and low densities—the conditions are just right for the s-process to create heavy elements. First, an atomic nucleus captures a single neutron, forming a heavier isotope of the same element. Because of the excess neutron, this isotope is typically unstable.

Through subsequent beta decay, one of the neutrons transforms into a proton, which remains in the nucleus and increases the atomic number by one. The original element is thus converted into a new element with the next higher atomic number. The electron created in the beta decay is ejected from the nucleus, as is a neutrino, which escapes the star at nearly the speed of light and vanishes into space.

A defining characteristic of the s-process is that the average time between neutron captures is longer than the time required for the unstable isotope to undergo beta decay and become a stable nucleus. The necessary conditions for this—cool temperatures and low densities—are present in these red giant stars.

In contrast to this slow neutron capture, there also exists a rapid neutron-capture process, the r-process (from rapid), which occurs only under extremely high neutron densities in certain types of supernovae.

References:

- P. W. Merrill: Stellar Spectra of Class S. Astrophysical Journal 56, 457-482 (1922)

- P.W. Merrill: Technetium in the Stars. Science 115, 484 (1952)

- P.W. Merrill: Spectroscopic Observations of Stars of Class S. Astrophysical Journal 116, 21-26 (1952)

- P. C. Keenan: Classification of the S-Type Stars. Astrophysical Journal 120, 484-505 (1954)

- B.F. Peery, Jr.: Technetium Stars. Astrophysical Journal 163, L1-L3 (1971)

- F. Käppeler, G. Martinez-Pinedo und F.-K. Thielemann: Der Ursprung der Elemente, Teil 2: Durch Neutroneneinfang zu den schwersten Atomkernen. Sterne und Weltraum, Dezember 2018, 36-47