In a previous article (Outsmarting Earth’s Atmosphere), we have already described how (and why) small telescopes and the lucky imaging method can be used today to obtain extremely sharp images of the moon, planets, and some brighter deep sky objects that were not even possible with large telescopes a few decades ago. But what about classic long-exposure photography of star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies (known as “Deep Sky Astrophotography”)? Here, too, there are completely new possibilities for instruments of all sizes…

When combining the terms Astrophotography and Hubble, two things probably come to mind for those interested in astronomy: on the one hand, the fantastic images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope, and on the other hand, Edwin Hubble’s revolutionary observations from about 100 years ago which changed our view of the cosmos, and which really justify the famous telescope being named after him. If we then add the “Co” from the title – namely the extreme capabilities of modern, Ground-based large telescopes – then some laymen may think that serious astronomical observations today only make sense if one have the largest equipment available.

But professional astronomy itself shows that this cannot be true. Today, cutting-edge research is conducted using both large telescopes and small camera lenses, because the instrument chosen depends, for example, on the research question and the characteristics of the target objects. In fact, there are countless objects for which a large telescope would be the worst possible choice for investigation. Conversely, there are celestial bodies that cannot be studied effectively with small optics. And the outstanding technologies in the field of cameras and sensors, which are used in all kinds of astronomical devices today, allow even small instruments to achieve performances that would have been unthinkable decades ago even with big telescopes. This applies to every purpose – to obtain impressive images, for training and teaching, and even for collecting “real and useful” scientific data.

Like the aforementioned article on lucky imaging, the following examples from the field of deep sky astrophotography are intended to give a small impression of “what is possible today.” Some examples push the limits and emulate Hubble (the telescope and the researcher), while others are not even that difficult.

But one thing must be mentioned in advance: due to mostly weak signals, astrophotography almost always takes place at the limits of detectability. The final images shown here are all the result of data acquisition and calibration standards commonly used in modern professional astronomy. Even Hubble Space Telescope’s raw data is noisy and initially far from the beautiful images we are often see in the media. But let’s get started…

Galactic nebulae – how "big" and "small" (optics) complement each other and how instruments become suitable for astronomy...

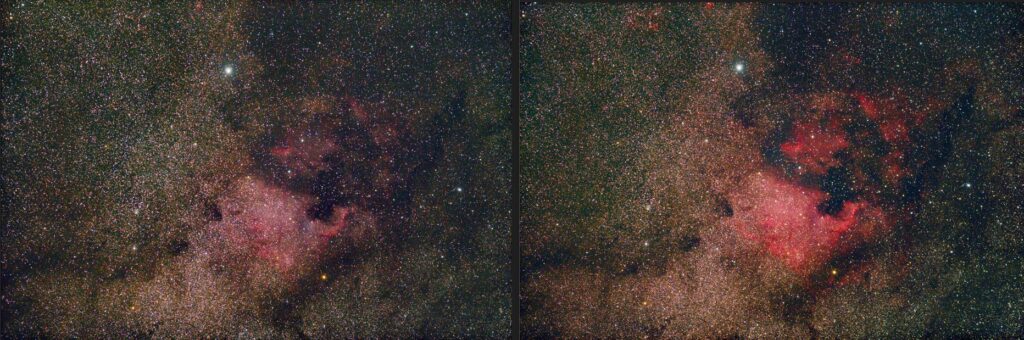

Figure 1 shows two images of the well-known North America Nebula NGC 7000, a star-forming region in our Milky Way. The image on the left was taken with a standard commercial digital SLR camera (DSLR) – in other words, with “off-the-shelf” technology – although in this case it was equipped with a telephoto lens with f=135mm and an extreme aperture ratio of f/2, which is highly valued in astrophotography circles for its light gathering power and excellent image quality, making it much easier to capture faint, extended objects like nebula. The total exposure time was only 20 minutes. This is possible primarily due to the quantum efficiency of the built-in digital CMOS detectors. In normal cameras, this is around 30-40 percent, meaning that a good third of the photons from an object that fall on the sensor are really captured. That may not sound like much at first, but in classic photography, the efficiency was only around one percent!

But with a relatively simple modification, it gets even better. In the image on the right above, taken with an almost identical setup (and immediately afterwards on the same night, i.e., with the same weather and air transparency!), the reddish glowing nebula stands out much more clearly. The reddish color is caused by glowing hydrogen gas, which emits light at a wavelength of about 656 nm and appears reddish to our eyes. However, this spectral range is largely filtered out by standard cameras (left image), because otherwise the colors in daylight shots would not correspond to what our eyes are used to see (the images would have a red cast). But in astrophotography of galactic nebulae, we naturally want to see these wavelengths. The camera in the right-hand image has therefore been astro-modified, i.e., the filter has been removed. With this small and comparatively inexpensive measure costing a few hundred euros only, a DSLR camera (or a mirrorless DSLM) can be turned into a decent camera for astrophotography.

Figure 2 also shows an image of the nebula taken with the 135 mm f/2 lens, but with two significant improvements: First, a dedicated astro-camera was used, in this case a even cooled camera to reduce thermal noise, with smaller and numerous pixels for high resolution and a quantum efficiency of approximately 85% (which is much better than a DSLR and close to perfection). Second, a narrow-band filter was used that only allows light around the OIII- and Halpha spectral lines (oxygen and hydrogen) to pass through – precisely the light emitted by many emission nebulae. All other wavelengths – especially also our artificial light from cities is filtered out.

Thus, this method allows such images to be taken even in areas with light pollution and increases the contrast.

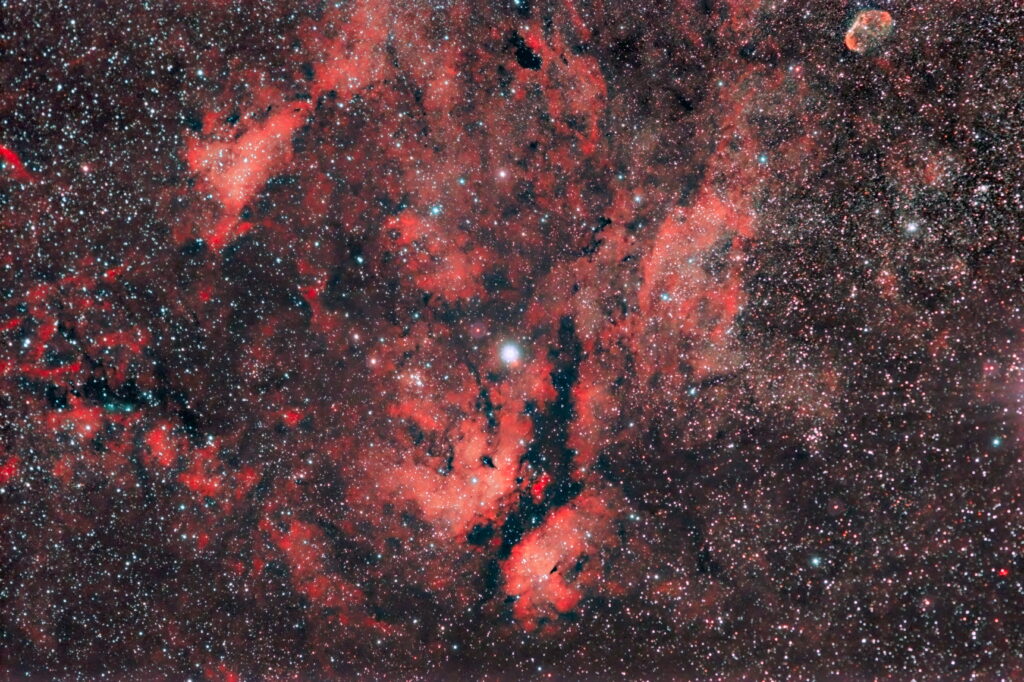

Figure 3, on the other hand, goes into great detail. NGC 7000 covers several full moon areas in the sky. In order to capture the entire nebula in its surroundings, even a medium-sized amateur telescope is usually completely “oversized” (a larger image scale usually goes hand in hand with a smaller field of view). The setups in Figure 1 and, above all, in Figure 2 are therefore ideal for capturing the entire nebula area. But figure 3 now shows a high-resolution section of the nebula in a quality that was only possible with large telescopes decades ago. The image has a total exposure time of only 60 minutes and was taken with the aforementioned combination of a cooled astro-camera and narrow-band filter, but this time mounted in the focus of a Newtonian reflector telescope with a 15 cm main mirror diameter and at f/3.45. The resolution is approximately 0.9 arc seconds/pixel.

Figure 4 shows another example of a wide-field image taken with the astro-camera, the narrow-band filter, and the 135 mm telephoto lens. Here you can see the structurally rich nebula complex around the star Gamma Cygni (center of image). At the top right, the so-called Crescent Nebula NGC 6888, located almost 5000 light-years away, can be seen – a nebula surrounding a Wolf-Rayet star. Nice, but a detailed view of this object alone requires completely different means.

Figure 5 shows the Crescent Nebula filling the frame, captured with an astro camera and narrow-band filter – but now installed on a modern Ritchey-Chrétien truss-tube reflecting telescope with a 254 mm aperture (see also the article on lucky imaging). Figures 4 and 5 both have an exposure time of approximately 50 minutes.

With these new possibilities, it is also worth photographing objects that have become very popular thanks to the Hubble Telescope. Figure 6 shows the famous “Pillars of Creation” in the nebula region of the open star cluster Messier 16. The image was again taken with an astro-camera, but this time on a small Newtonian reflector telescope with an aperture of only 13 cm.