A little over 100 years ago, Edwin Hubble ended a long and controversial discussion among ex-perts that went down in history as the “Great Debate” and opened the door to cosmology by answering “yes” to the following question: Are some of the nebulous astronomical objects not gas clouds in our own Milky Way, but independent galaxies far outside our Milky Way system? Hubble provided the proof because he had access to the new 2.5-meter reflecting telescope on Mount Wilson in California, which was the largest and most sensitive telescope in the world at the time, to take long-exposure photographic plates. This enabled him to detect individual stars (which are very faint due to their distance) in the Andromeda Nebula Messier 31, proving that the object is indeed an independent galaxy at a distance of approximately 2.5 million light-years.

Today, this experiment is relatively easy to replicate with small instruments (and is actually a nice experiment for physics classes).

Figure 7 shows part of the Andromeda galaxy photographed with a 15 cm Newtonian reflecting telescope. Highlighted is the star cloud NGC 206, consisting of many so-called OB stars, i.e., luminous blue stars that are reasonably easy to photograph despite their great distance. A brief consideration shows why this is so easy today: as mentioned above, the modern detectors in an astro-camera are about 100 times more sensitive than Edwin Hubble’s photographic plates were back then. This roughly compensates for the difference in light-gathering power due to the mirror sizes used (for example, a 2-meter telescope collects 100 times more light per unit of time than a 20-cm telescope). In addition, modern detectors are linear, meaning that doubling the exposure time also doubles the signal measured. Classic analog and chemical photographic material is subject to the so-called Schwarzschild effect, meaning that sensitivity appears to decrease with increasing exposure, which is why much longer exposure times are required to double the signal, for example.

Thanks to the techniques available today, other amazing things are possible with small equip-ment. Here is another example.

Figure 8 shows the spiral galaxy Messier 33, also approximately 2.5 million light-years away, in a one-and-a-half-hour exposure taken with the same 15 cm telescope. This time, however, a duo narrow-band filter was used again to specifically measure the light from emission nebulae – sim-ilar to the gas nebulae in our own Milky Way (Figures 2 to 5). In addition to the fact that many faint individual stars are also visible in the spiral arms of this galaxy, the numerous reddish glowing star-forming regions are visible. So here we see individual objects like those in our galaxy – but now millions of light-years away and, on closer inspection, still with numerous morphological de-tails.

The challenge increases – photographing details in distant active galaxies

Among the most exciting extragalactic objects are undoubtedly active galaxies – star systems with active core regions around their central, matter-accreting, supermassive black hole, often associated with massive star formation (starbursts), high energy jets that are usually only detect-able in the radio range, or disturbed morphology due to interaction or merging with neighboring galaxies. Although not all objects of this type are classic quasars with high redshifts and thus at large cosmological distances, one has to go a little “further out into space,” and such objects are more typical targets for large telescopes when one wants to examine specific details.

Here, too, interesting experiments can be carried out today “in your garden” with the appropriate equipment, but the telescopes should not be too small. Here are three exciting examples.

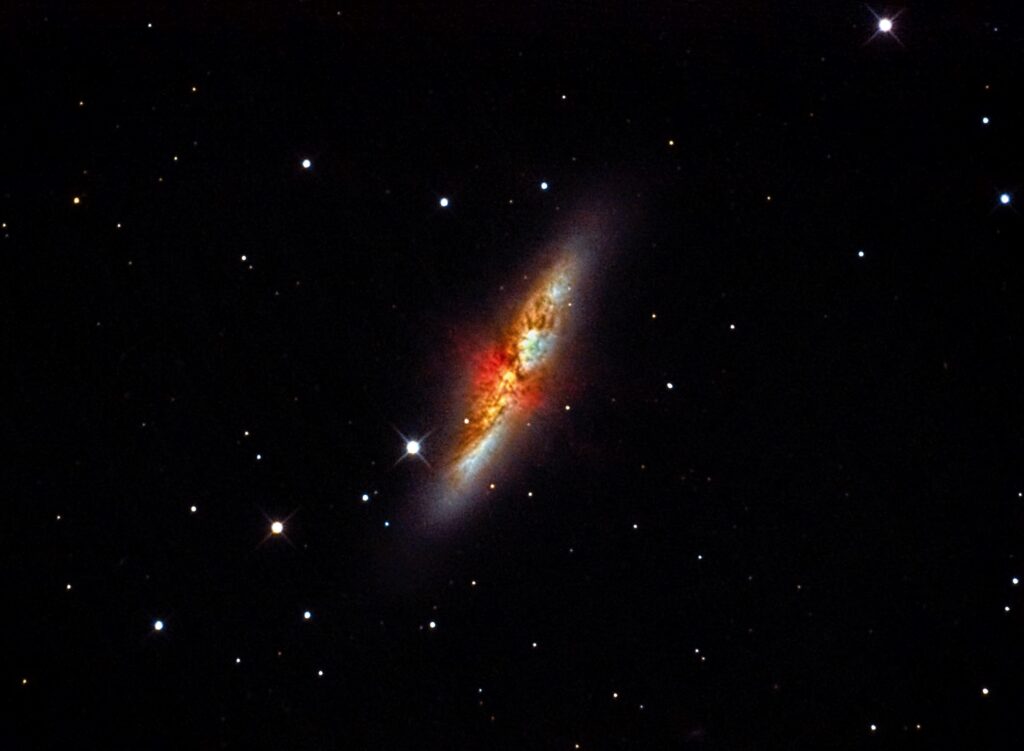

Figure 9 shows the starburst galaxy Messier 82, which is still relatively close at a distance of 13 million light-years, where numerous supernova explosions cause turbulence and strong outflows of gas from the galactic plane over tens of thousands of light-years. The image was taken with a 25 cm Ritchey-Chrétien reflecting telescope by combining a classic 3-color image with an image taken with an OIII/Halpha dual narrow-band filter to highlight the outflows and morphological features. This image can easily compete with earlier images taken with much larger telescopes a few decades ago.

The image of the peculiar galaxy Arp 299 shown in Figure 10 was also taken with the same telescope and the same methodology. It is amazing how much detail can be captured of the active regions and the morphological disturbances caused by the interaction of a pair of galaxies, be-cause this object, with a light-travel distance of 150 million light-years, is more than 10 times farther away than Messier 82 and is a typical object of study in all wavelengths for large telescopes on the ground and in space (see also https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arp_299).

Another challenge for technology can be seen in Figure 11. It shows the central region of the quasar-like active giant galaxy Messier 87 in the Virgo galaxy cluster (distance approx. 60 million light-years).

With the help of rather short individual exposures (30 seconds each), the core area is not over-exposed by the extended galaxy. With good seeing conditions, it is now possible even with small telescopes to photograph the high-energy jet from the central area of the black hole on the final added image (here seven minutes exposure time in total). A few decades ago, anyone attempting to photograph the jet without a large telescope would have been ridiculed. Due to its remarkable properties, Messier 87 has been one of the central objects of research in astrophysics for many decades and in all spectral ranges (see also https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Messier_87).

Making the impossible possible

Nowadays, it is actually possible to penetrate cosmological distances and photograph distant galaxy clusters with relatively small telescopes. A relatively easy exercise is to photograph areas of the Virgo galaxy cluster at a distance of approximately 60 million light-years (Figure 12).

More remarkable (yet still relatively easy) is photographing the Coma galaxy cluster Abell 1656 at a light-travel distance of just under half a billion light-years – shown in Figure 13.

With the exception of a few foreground stars from our galaxy, most of the numerous objects in the image are galaxies in the cluster—mostly elliptical or spindle-shaped Milky Way systems. After all, Abell 1556 was considered the most distant known object in astronomy until the dis-tance to the quasar 3C273 was determined in the 1960s for the first time.

With regard to the morphology of the cluster galaxies, a comparison with Figure 14 is interest-ing.

Here you can see an area of the Hercules galaxy cluster Abell 2151, which is also about half a billion light-years away. In contrast to the Virgo and Coma clusters, this cluster contains a large number of spiral and, above all, interacting galaxies – no problem to detect today with a 25 cm telescope and only one hour of exposure time (so far only a snapshot) with an astro-camera, provided the equipment meets certain technical standards. Abell 2151 is certainly a worthwhile target for a very long exposure.

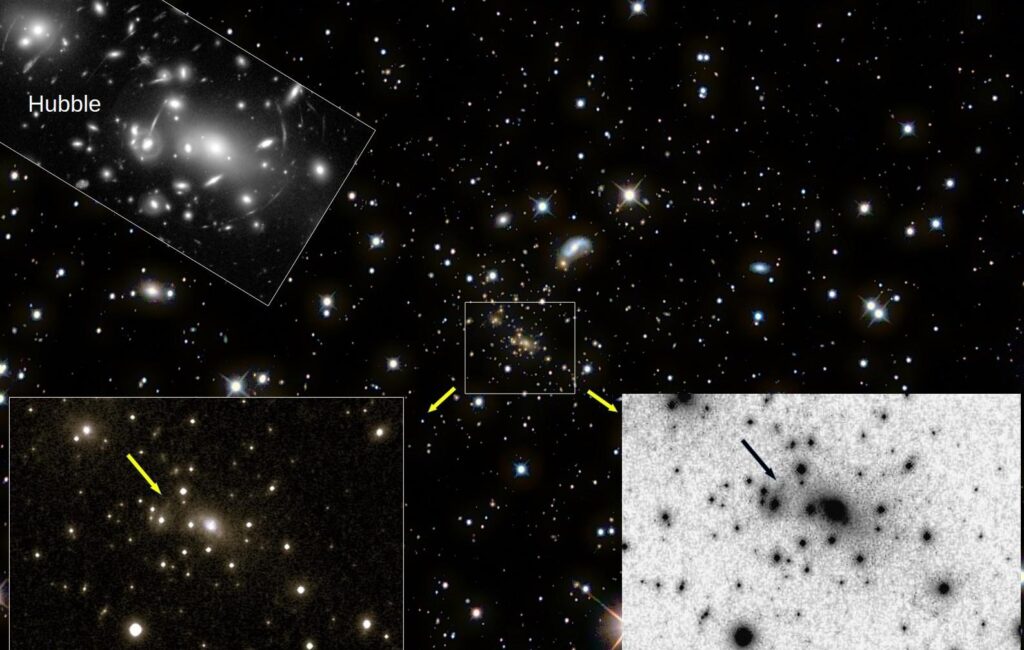

Finally, here is the result of a project that goes far beyond what is usually considered feasible with small telescopes. The successful attempt is documented in Figure 15.

One of the most famous images from the Hubble Telescope is that of the galaxy cluster Abell 2218, located about 2.1 billion light-years away, which acts as a gravitational lens and makes galaxies even further away visible. Some of them are recognizable in the form of gravitational lens arcs. The task was: Is it possible to photograph this cluster with a 25 cm telescope from a light-pol-luted location with rather poor seeing and still clearly recognize such gravitational lens arcs? The answer is “yes,” as Figure 15 impressively demonstrates.

The total exposure time of the image shown here is approximately 11 hours up to this point. The marked arc has a total brightness in the range of 21st to 22nd magnitude and a redshift of about z=0.7 (Pelló et al., A&A 266:6-14, 1992). This means that the galaxy seen here through Abell 2218 is located at a light-travel distance of approximately 6.3 billion light-years (according to ΛCDM standard cosmology).

This last example in particular shows that with today’s technical capabilities, amazing things are possible even with relatively small telescopes and in less than ideal locations. This has already been demonstrated in our article on lucky imaging.

With our much more powerful Webservatory® telescopes, which are also located at top astronomical sites, we offer you access for your own challenging projects.