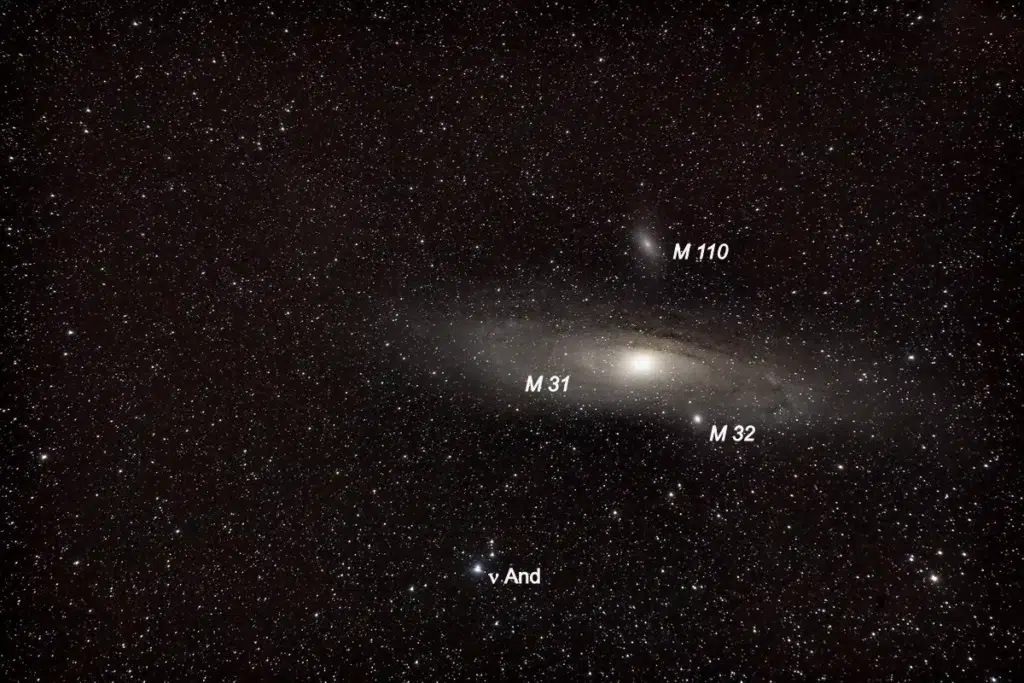

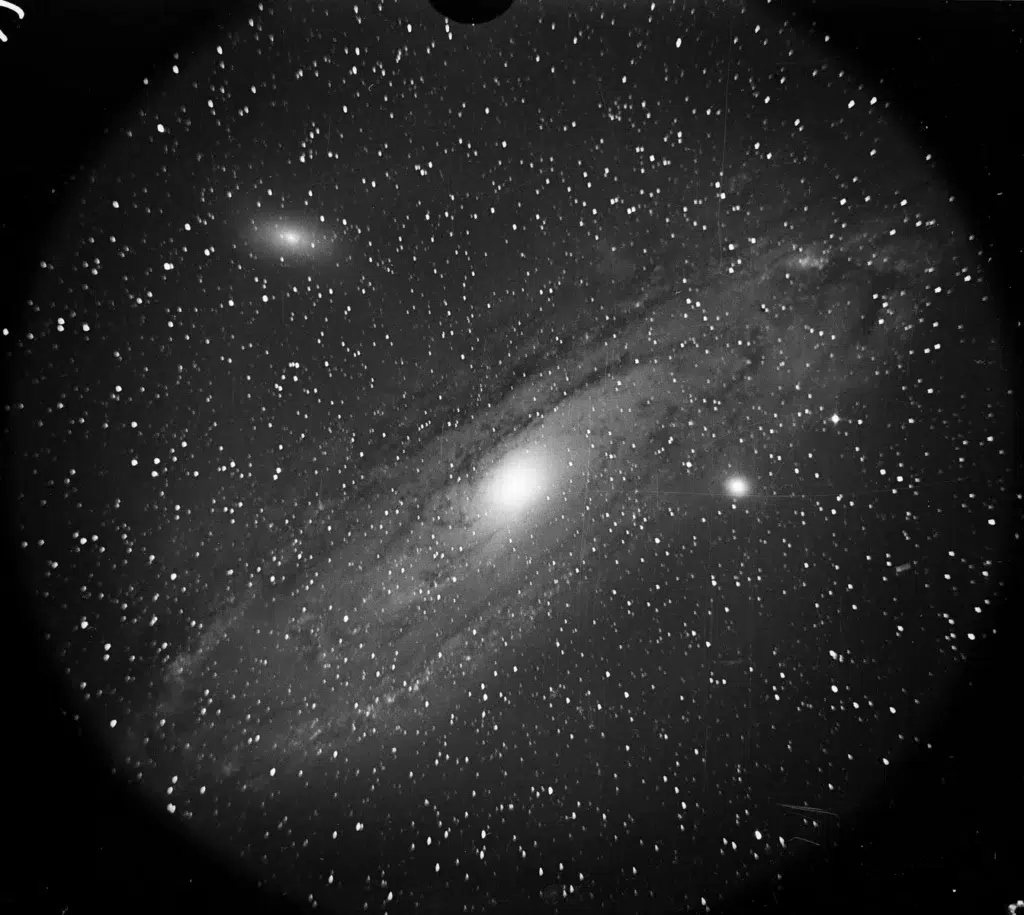

Under a dark sky, the Andromeda Galaxy (M 31) can be seen with the naked eye. However, only its bright central region appears as a faint, diffuse patch of light. Its enormous dimensions become apparent only in long-exposure photographs: its major axis extends 3.3°, more than six times the diameter of the full Moon. Long, elongated dark dust lanes can be seen between its spiral arms. Like our own Milky Way, the Andromeda Galaxy also has two companions: the small stellar systems M 32 (NGC 221) and M 110 (NGC 205).

We locate the Andromeda Galaxy by extending the line connecting the stars Beta Andromedae (β And) and Mu Andromedae (μ And). At a distance of 2.5 million light-years, it is the most distant object visible to the unaided human eye. Considering how easily it can be recognized, it is somewhat surprising that no records of it survive from antiquity. The earliest known mention of the Andromeda Galaxy comes from the Persian astronomer ʿAbd al-Rahman al-Sufi (903–986), who described it as a “small cloud” in his Book of Fixed Stars and marked it in his illustration of the constellation Andromeda as a cluster of black dots.

In the Western world, Simon Marius (1573–1624) drew attention to this diffuse object, which he observed with a telescope in 1612. Because he could not resolve any individual stars, the term Andromeda Nebula became established. For a long time, the true physical nature and distances of the various nebulous objects in the sky remained unclear. A definitive distinction between gaseous nebulae within our Galaxy and independent stellar systems—galaxies—was not achieved until the 1920s.

Using what was then the world’s largest telescope, the 2.5-metre reflector at the Mount Wilson Observatory in California, the astronomer Edwin Hubble discovered Cepheids in the “nebulae” Messier 31 and Messier 33 in 1923. Thanks to the period–luminosity relation of Cepheids, discovered in 1912 by Henrietta Swan Leavitt, it became possible for the first time to determine the distances to these objects. This proved conclusively that they are independent galaxies located outside our own Milky Way.

NGC 891: Seen Edge-On

NGC 891 is a spiral galaxy in the constellation Andromeda with a particularly striking appearance: we view it directly edge-on, so it appears as a narrow streak in the sky. The prominent central bulge, characteristic of such galaxies, is clearly visible. Equally distinctive is the dark band of gas and dust along the galactic plane, extending across the full length of the galaxy.

Galaxies seen edge-on provide an excellent opportunity to study both the radial and vertical structure of a spiral galaxy and to investigate its various components. The distribution and motions of the stars reveal information about the galaxy’s formation history, since many dwarf galaxies have merged over time to form the large stellar system we see today. The interstellar matter—composed of gas and dust clouds—offers clues to gravitational instabilities. Because of the low temperatures of this interstellar material, such studies are conducted primarily in the infrared and submillimetre wavelength ranges. The chemical composition of the dust, which appears as prominent dark lanes in visible light, is inferred from its emission and absorption spectra.

At a distance of 31 million light-years, NGC 891 is close enough to serve as an ideal research object. Although its exact spiral subtype cannot be determined due to the edge-on orientation, many scientists consider NGC 891 a Milky Way analogue because of its morphology and rotational behavior—making it a valuable comparison object for our own Galaxy.