Lucky Imaging makes it possible to take sharp images of the sun, moon, planets, and double stars even with small telescopes, which was impossible just a few decades ago even with the best and largest telescopes in the world. And in some cases, the technique can also be used, at least in a slightly reduced version, to capture some of the faint so-called Deep Sky Objects – i.e., objects such as star clusters, galaxies, or gaseous nebulae, which are normally only associated with long-exposure images.

But how does Lucky Imaging work?

Part of the answer is already part of the above description of the Seeing. The image of a star, which jumps back and forth in the millisecond range but is sometimes sharp for a very brief moment, adds up to the usual more or less extended round stars at normal exposure times, as we know them from normal longer exposed images.

But what if, instead, you could save individual exposures in the millisecond range and then take only the best images and add them together so that they overlap? You would have a much sharper image of the object – ideally, even an almost diffraction-limited result.

And that’s basically how it’s done. This is made possible by modern, highly sensitive digital astronomical cameras in combination with software, such as we use on the Webservatory telescopes. The high sensitivity of these cameras allows exposures in the millisecond range and thus many thousands of individual images in a few minutes. This is basically equivalent to a high-resolution video, whose individual images are then analyzed retrospectively and, depending on certain criteria, either used or discarded.

Utilized means that in the first step, the individual images are sorted according to their sharpness. Then the images are centered (this is called registration) so that the so-called tip-tilt – the bouncing back and forth – is corrected (relative to a reference image, the object is then always in the same position). Finally, depending on the quality of the individual images, a decision is made as to what percentage of the best images to combine (average). The result is a much sharper image than would have been possible with average seeing conditions. With already very good Seeing conditions, sufficiently bright objects, and an extremely large number of very short individual exposures, it is even possible to come close to the diffraction limit of the telescope. The individual images are still very noisy, but averaging increases the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N ratio) with the square root of the number of averaged images.

Example: you have taken 9000 individual images, each with an exposure time of 5 ms. You decide to use the best (sharpest) 10 percent – i.e. 900 images. This improves the S/N ratio by a factor of 30 compared to a single image.

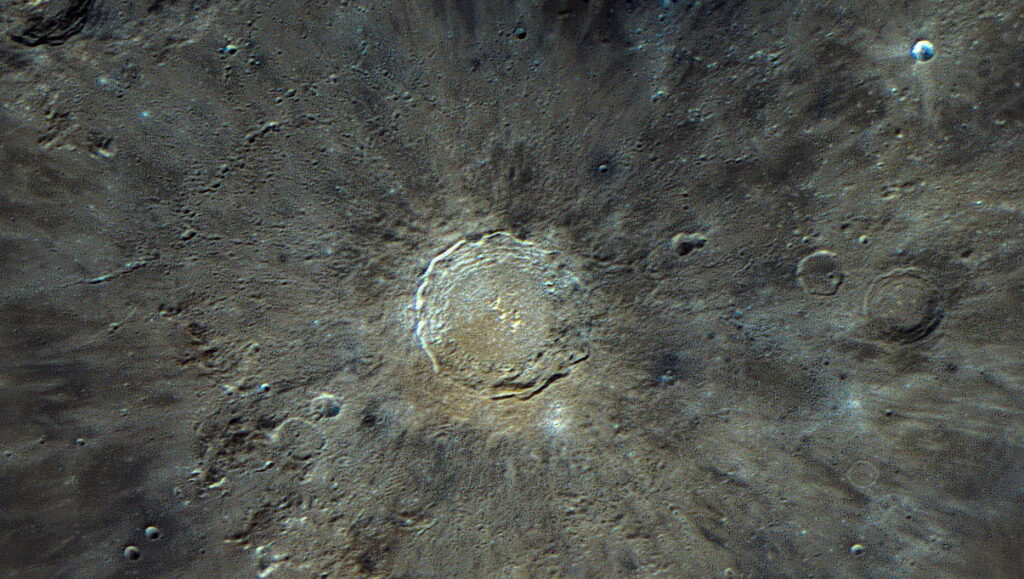

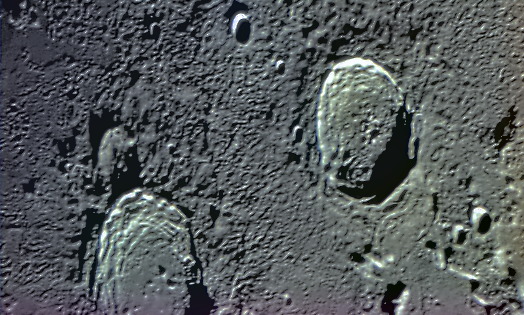

The following images show sample images taken using the lucky imaging technique.

Figure 6 a-d: High-resolution images of the moon taken with the author’s 25 cm RC telescope, the lucky imaging method, and the ASI ZWO 183 MC Pro astro camera. With a very large object such as a lunar region , the local seeing varies greatly from frame to frame depending on the image area. In a single image, for example, an area at the top left may be very sharp, while elsewhere it may be rather poor. And in one of the subsequent images, it may be exactly the opposite. To combine the final image, the quality is therefore measured regionally in each individual image and an individual quality sorting is carried out for each region. The final image is then assembled like a mosaic from the best 10 percent of each region, for example. This is what makes the above images possible.

Lucky Imaging for Deep Sky Objects too?

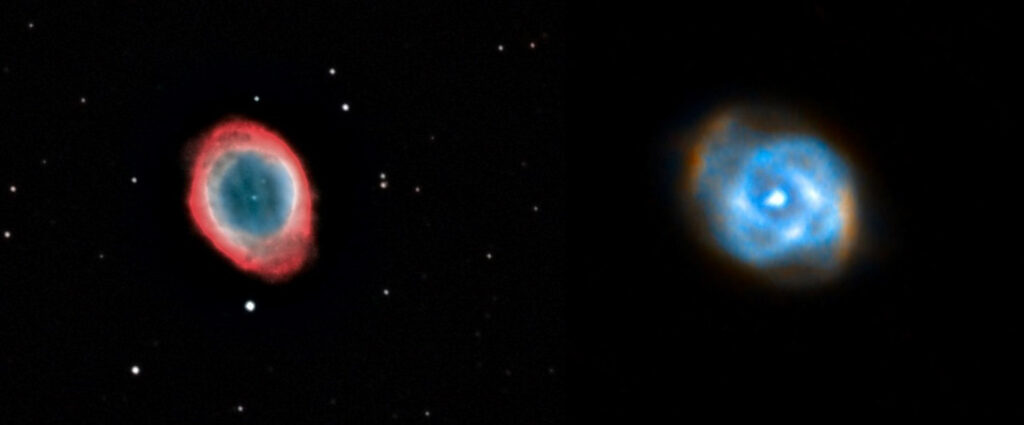

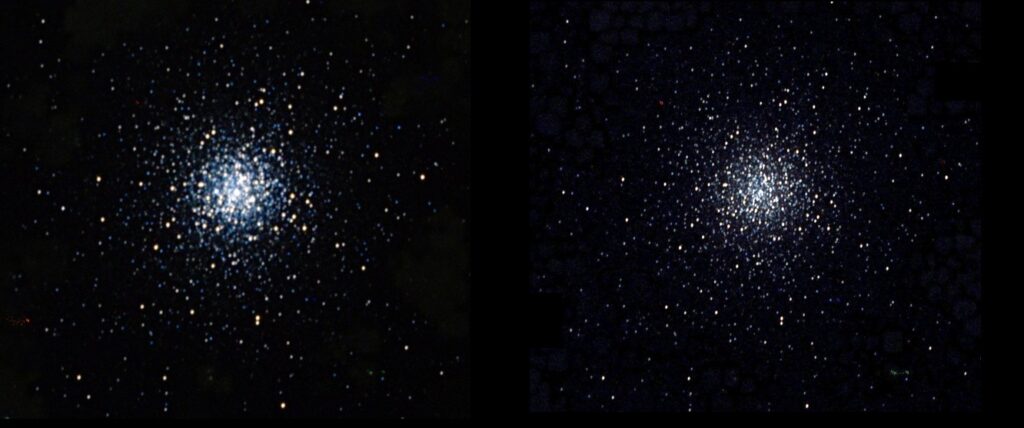

The high sensitivity of today’s special astronomical cameras makes it possible to use a slightly modified form of Lucky Imaging for deep sky objects as well. Modified because star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies are much fainter than the moon and planets. Extremely short exposures in the millisecond range are therefore pointless for these objects, especially with smaller telescopes. However, for brighter objects, you can try exposure times ranging from a few tenths of a second to a few seconds and take thousands of images again. In fact, even with exposure times in this range, there are still noticeable differences in the quality of the individual images, and a significant proportion are still significantly better than classic long exposures. By selecting and centering the best individual images in a similar way to “proper” Lucky Imaging, a relatively low-noise image can be produced by adding them together over a long total exposure time (minutes to hours), which is significantly sharper than classic long exposure. This works as long as at least one reference star or brighter parts of the object are still recognizable on the naturally extremely noisy individual frames to enable (software-based) quality detection, selection, and centering/registration of the individual images used.

Planetary nebulae or the centers of globular clusters are good targets for this method. Finally, here are a few examples:

The Webservatory interface for remote observation at our telescopes in Chile and Namibia, together with the highly sensitive and fast cameras, also allows all parameters necessary for Lucky Imaging to be set.